Toward a Definition of Children's Literature

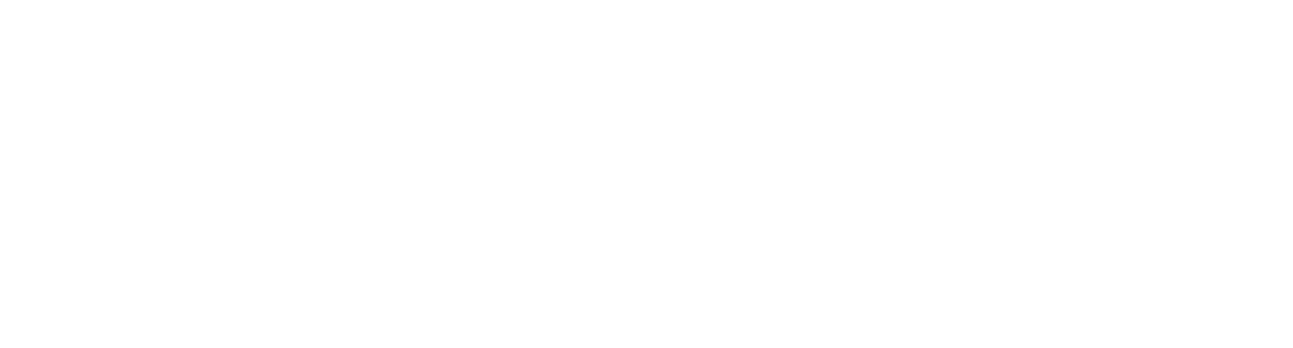

/This morning I read an engaging rant on a topic close to my heart: Whither the children's book?[1. thanks to Fuse #8 for pointing me to the story!] The post came from Australian Judith Ridge's excellent book blog, Misrule. "Misrule" is the name of a cluttered, sprawling home (think Von Trapp family crossed with the Lost Boys) in Ethel Turner's Australian classic Seven Little Australians.[2. Seven Little Australians is a delightful book that, along with The Paper Bag Princess (Canada) and The Wonderful Adventure of Nils (Sweden), seems to have been relegated to "local favorite" rather than part of the larger international canon. This is a pity.] Mary and I have, in fact, long dreamed of one day christening our own home "Misrule" and then filling it with lots of ill-mannered children.

Ridge's post bemoans what she sees as a trend in the book industry of labeling books written for children as "Young Adult" ... some even going so far as to call chapter books "Young Young Adult." This is obviously a market-directed phenomenon, and thus something that will pass after a few more YA movies flop at the box office[3. Note how Cowboys vs. Aliens and The Walking Dead are not being touted as a comic book adaptations -- quite the change from five years ago when everything was boasting its comic creds.]

Ridge's post bemoans what she sees as a trend in the book industry of labeling books written for children as "Young Adult" ... some even going so far as to call chapter books "Young Young Adult." This is obviously a market-directed phenomenon, and thus something that will pass after a few more YA movies flop at the box office[3. Note how Cowboys vs. Aliens and The Walking Dead are not being touted as a comic book adaptations -- quite the change from five years ago when everything was boasting its comic creds.]

Of course, this new trend begs an old question: what is children's literature? It's a slippery question because for every rule you put down (Rule #1: "Children's Books Feature Child Protagonists"), you can find an adult book featuring the same trait.

After many years of wrestling with this definition, I came across one trait that might actually apply to every children's book ... and is virtually antithetical to adult literature. It is something my wife (who studies Victorian children's literature) learned while working with children's literature scholar June Cummins. Are you ready?

children's literature assumes a teachable audience

This is not limited to books with obvious morals. Nor does it specify that this "teachable audience" must be a literal child. Rather, it specifies a tone in which the author is speaking to a reader who is still unformed in his/her opinions.

I understand that this is an infuriatingly-vague definition. It's akin to "defining" comedy as being anything that's funny. But unlike the a posteriori checklists obsessed with reading level and plot specifics, Cummins' definition is both parsimonious consilient.[4. Which my freshman geology course instructed me was essential for any good scientific theory! Go college!]

What really excites me about this definition is that it might also be applied to YA books ... and it goes a long way toward explaining why some Young Adult titles feel like adult books and others feel like children's books.